Star Wars is, undoubtedly, one of those treasures. Popular culture swallowed it whole and happily when it was released in 1977. A massive marketing campaign, complete with toys, T-shirts, and lunchboxes was launched to seize the opportunity to turn a tremendous profit from the fad. These events need hardly be recounted, indeed, they should be common knowledge. However, what is interesting is that Star Wars maintained a sort of cult following in the years following The Return of the Jedi. Although there had long been Star Trek fandom, a strange, counter-culture began to develop based not on Kirk's but on Lucas' enterprise.

This fringe group cleaved to the imaginative Star Wars universe. In the absence of films, comic books and novels began to be released. These represent the explorations of fans in the universe that George Lucas had evoked. Some of these forays sought to reveal the origins of the Sith, the early years of the Republic, and to gradually fill out the galaxy far, far away with races, planets, corporations, spacecraft, and people.

Into this milieu, amidst special re-releases of his trilogy, Lucas announced the story of Anakin Skywalker would be told v

ia three prequel films. Excitement built to near-hysterical levels until the day The Phantom Menace was released. Although the general public enjoyed the movies, a large portion of the fans, many of whom had contributed to the universe through their own publications as novelists and comic book artists, had watched the original films in the theaters as children, and had grown up thinking they knew Star Wars, were suddenly thrown into a world they did not recognize. Grumblings of discontent flamed into outright hatred. Fans rarely had a choice to remain ambivalent--the prequels were either travesties upon Lucas' vision and the proverbial axe which "killed the goose that laid golden eggs." The masses consumed the prequel trilogy as readily (if not moreso) than they had devoured the original films, thus the goose can be seen to have continued to lay away, happy and healthy.

ia three prequel films. Excitement built to near-hysterical levels until the day The Phantom Menace was released. Although the general public enjoyed the movies, a large portion of the fans, many of whom had contributed to the universe through their own publications as novelists and comic book artists, had watched the original films in the theaters as children, and had grown up thinking they knew Star Wars, were suddenly thrown into a world they did not recognize. Grumblings of discontent flamed into outright hatred. Fans rarely had a choice to remain ambivalent--the prequels were either travesties upon Lucas' vision and the proverbial axe which "killed the goose that laid golden eggs." The masses consumed the prequel trilogy as readily (if not moreso) than they had devoured the original films, thus the goose can be seen to have continued to lay away, happy and healthy.But for some, Star Wars was ruined. Lucas had killed it. What had originally begun as a great Wagnerian saga in space had become "kid's stuff." But is this truly accurate? Did The Phantom Menace truly "kill" the Star Wars universe? Besides, what does it mean to actually "kill" an imaginary universe? How can Star Wars be any more dead than Cervantes' Don Quixote or Homer's Iliad? So long as the story and the setting are remembered, it must survive in a way.

The sense of betrayal, however, comes from feeling that Lucas had created something much more substantial, and then debased it. It is as if took a gold doubloon, and instead of keeping it, melted it down and mixed it with enough copper to produce three or four "gold" coins. Or perhaps it is as if Raymond Chandler had decided, after a break, to take up his pen again and instead of writing Philip Marlowe story scrawled a dull and predictable Hardy Boys paperback and expected his fans to enjoy it.

However, is this an accurate assessment of Lucas' creation? Besides, it is, after all, Lucas' own world, his own story? Can he not change it as he sees fit? Fortunately for you, dear reader, I shall abstain from waxing philosophic, and avoid coma-inducing discussions on postmodern literary criticism and the death of the author. I will, however, encourage one to read The Secret History of Star Wars for a frank and unbiased account of Lucas' own eccentricity (which fame and fortune has perhaps brought near to dementia).

The crux of my discussion is that Star Wars has not been "killed" by The Phantom Menace, nor any of the other prequel films. Indeed, the saga survives through its adoring fans and through the continuing production of cartoon episodes and films (despite the occasional insubstantial and disappointing plot and dialogue). However, it has been transformed. Indeed, through his Orwellian attempts to rewrite history (again, see The Secret History of Star Wars), Lucas has even managed to transform the very conception of the original trilogy from the saga of Luke Skywalker into the redemption of Anakin Skywalker. Many feel that, by transforming Star Wars, the original vision of what Star Wars had been is now dead, and indeed, that most certainly is the case. However, I do not pinpoint the death of that original vision to have been The Phantom Menace. A horde of Jar-Jar Binkses could not kill what is already dead, nor could a "whiny teenage Anakin Skywalker," any more than Ewan McGregor, Christopher Lee, or Liam Neeson could resurrect it (though they made commendable efforts).

That original vision was killed by Leigh Brackett when she penned the script for The Empire Strikes Back.

---

To understand how Brackett murdered Star Wars, one must examine Lucas' purpose for creating the original film.The original movie was by no means a very original work. In all honesty, it was immensely derivative. That is, by no means, a flaw in the story. The entire film is cliché, but well written cliché (or if you prefer, trope). Those literary tropes were essential to Lucas, enabling him to tell precisely the sort of story he desired.

Let's isolate what Lucas had wanted to achieve with Star Wars:

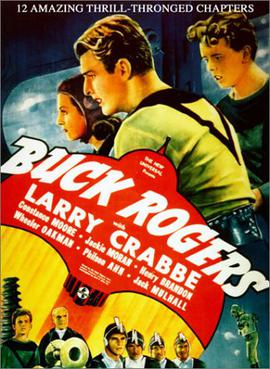

1. He aimed to show an episode, in media res, of a space pulp serial à la such pulpy serials as Flash Gordon or Buck Rogers. He wanted space ships, dogfights, laser swords, weird aliens, daring rescues, narrow escapes, and everything that would have made an excellent Flash Gordon episode.

2. He wished to tell a good story. Inspired by Joseph Campbell, Lucas utilized a number of tropes that would develop a compelling heroic tale, including a family heritage, a young hero, a black knight, a mystic power, a wise mentor, damsels in distress, etc.

The original Star Wars was a success on all counts. Not only did it committ Lucas into the annals of science-fiction history for all time, enrich him and the motion picture industry, the film accomplished precisely what he had intended. It is an exciting film with elegant pacing, juxtaposing smooth plot and character development with lively science-fiction and fantasy action sequences. Each scene presents the viewer with something to rivet his attention, be it a new robot, a strange lifeform, a vehicle, or some source of danger or tension. Even expository scenes, where plot is introduced and characters developed, strange and interesting aspects of the universe are presented to intrigue the viewer on a visual and visceral level, and pull him into the scene.

The plot itself is divided well, with a prologue (the battle above Tatooine), three acts (Tatooine, the Death Star, and the Battle of Yavin), and an epilogue (the awards ceremony). Throughout these acts, we watch our youthful hero, Luke Skywalker, develop from an innocent, inexperienced farm boy into a great pilot and warrior. A dark knight is introduced, Darth Vader, who is responsible for the death of Luke's father, and subsequently, the death of his mentor. The film is often compared to Kurosawa's The Hidden Fortress, for the two films share many literary tropes.

Star Wars is a fantastic study in cinema craftsmanship. It is a perfect (in the sense of completion) product. All the dross has been swept away and left on the cutting room floor, leaving nothing but a refined, glistening reel. It is not pretentious. It doesn't take itself too seriously, but just seriously enough. It is to the space opera what Raymond Chandler's The Big Sleep is to a hardboiled film noir. It is cool and confident in what it is. Star Wars does not present us with moral quandaries or ethical dilemmas. The heroes overcome their challenges through virtue. Courage and friendship are enough to overcome the greed and cynicism of the Empire. Although outgunned and outnumbered, the Rebel Alliance, with Luke's help, have a chance of overthrowing the tyranny of the Empire because of the bravery of the main characters, Luke and Leia, Chewbacca and Han. Good and evil are sharply defined. There is no grey area, no ambiguities. Darth Vader is "a master of evil" and Obi-wan represents selfless sacrifice for a cause. It is the ultimate heroic yarn, only set in space.

The Empire Strikes Back is

an entirely different animal. If Star Wars is like The Big Sleep, then The Empire Strikes Back is like L.A. Confidential or Roman Polanski's Chinatown. Whereas the first Star Wars had a purely linear plotline, The Empire Strikes Back divides the action after the Battle of Hoth, sometimes following the exploits of Han and Leia while they flee from the Empire, and other times chronicling Luke's rigorous training. Throughout the story, the characters and their depth become much more challenging to the viewer.

an entirely different animal. If Star Wars is like The Big Sleep, then The Empire Strikes Back is like L.A. Confidential or Roman Polanski's Chinatown. Whereas the first Star Wars had a purely linear plotline, The Empire Strikes Back divides the action after the Battle of Hoth, sometimes following the exploits of Han and Leia while they flee from the Empire, and other times chronicling Luke's rigorous training. Throughout the story, the characters and their depth become much more challenging to the viewer.Why does Vader fanatically pursue The Millenium Falcon with the strength of an entire Imperial war fleet? Why is he so obsessed with finding Luke Skywalker? Shouldn't he be busily hunting down the escaped Rebel fleet to finish them once-and-for-all? Why is it more important to capture Han Solo and Princess Leia so he can lure Luke into a trap?

The original film doesn't inspire so many questions. That is because it is far more simple and straightforward. However, its sequel is more dynamic and demands more from its audience than simple passive viewing. It demands an emotional investment.

The training that Luke undergoes is strenuous. Suddenly, we see him doubt himself. The good, honest, hardworking young hero that we saw in the initial film has turned into an impatient, aggressive, reckless avenger. Suddenly, he is no longer the "model hero" that he had been in Star Wars. As Yoda trains Luke, our hero's experience and "failure" in the cave forces not only Luke to question himself, but us to question him as well. Before, we were only worried that a lucky laser blast might kill him. Now, we are worried that Luke might actually be capable of falling because of himself. This is a tremendous shift in both tone and temperment.

The rising tension culminates with the tremendous sense of treachery and the development of moral and ethical ambiguities. Lando Calrissian is forced to betray Han Solo in order to preserve Cloud City, and realizes that it was all in vain. Han and Leia's bourgeoning love is cut short by his encasement in carbonite. And, possibly most importantly and traumatically, Luke learns that Obi-wan, that wise, serene, selfless sacrifice of the first film, had lied to him regarding the fate of his father. All of the formerly clear, distinct lines between right and wrong are now blurred, indistinct. Who is a friend, who is a foe? Why would Obi-wan lie? Once you begin to question, you cannot stop--you can only follow the quandaries down the slippery slope to the inevitable "what if the Rebel Alliance is wrong and the Emperor is right?"

This is not like a Buck Ro

gers or Flash Gordon episode. There was never any doubt in Flash's mind that Ming is as Merciless as his epithet implies. He is constantly confident in himself and his ability to wage the great fight against his enemy. He is the quintessential hero--more than human, a demigod. In contrast, Luke has just been defeated in battle and has certainly fallen short of full-fledged demigodhood. The schemes of the Emperor and Darth Vader have actually borne fruit, despite all of the valor and moral virtue that Luke and his friends could muster. The entire universe had been overturned--not just the universe that plays setting to the saga, but the very concept that Lucas had established. The tone of the series has radically diverged from that of a straightforward serial.

gers or Flash Gordon episode. There was never any doubt in Flash's mind that Ming is as Merciless as his epithet implies. He is constantly confident in himself and his ability to wage the great fight against his enemy. He is the quintessential hero--more than human, a demigod. In contrast, Luke has just been defeated in battle and has certainly fallen short of full-fledged demigodhood. The schemes of the Emperor and Darth Vader have actually borne fruit, despite all of the valor and moral virtue that Luke and his friends could muster. The entire universe had been overturned--not just the universe that plays setting to the saga, but the very concept that Lucas had established. The tone of the series has radically diverged from that of a straightforward serial.Leigh Brackett’s script had seized Star Wars and demanded it to change into something higher and more meaningful than a simple “clash of good and evil.” While writing The Empire Strikes Back, she brought forth her considerable talents as a science-fiction author. One of the vehicles of science-fiction is exploring the implications of moral and ethical dilemmas that might be presented by advanced technologies and knowledge. These issues comprise the kernel around which any good science-fiction story can build itself. Thus, it is why Isaac Asimov’s Foundation books were so fantastic, as well as Orson Scott Card’s Ender’s Game. Leigh Brackett may have been so steeped in science-fiction authorship that she was incapable of writing a simple episode in a heroic duel between good and evil. It is entirely possible that she felt the overwhelming need to turn Lucas’ universe on its ear for the express purpose of exploring what those characters would do when faced with treachery and defeat.

In so doing, Brackett’s The Empire Strikes Back emboldened viewers and fans alike with the possibilities of the Star Wars universe. She created a set of expectations for the audience that the original Star Wars could not live up to itself. Overall, The Return of the Jedi is a satisfying conclusion to the trilogy. It resolves Han Solo's debt to Jabba and subsequent capture by Boba Fett early on, and with a good deal of excitement. Luke Skywalker has reached a level of self-assurance and control due to his training and experience fighting Vader. He walks the thin grey line between good and evil.

That singular resolution of character development is proof that The Empire Strikes Back had thrown Star Wars upon its procrustean bed. That unambiguous divide between light and darkness presented in the initial film had been blurred. Luke's brush with the Dark Side and his battle with Vader have taken something from him. He dresses in black. He speaks in grave ultimatums ("Jabba, this is your last chance. Free us or die."). He is torn between his desire to redeem his father and the possibility that he may fall to the Dark Side if he does not kill him. He has become a much darker character, even though his outward appearance projects the calmness and serenity of a bodhissatva.

However, many of the elements of a Flash Gordon serial persist. There are kitschy elements found throughout The Return of the Jedi. They seem somewhat subdued, however. The tension is higher and the mood of the film is much more serious than the original movie. The building tension takes on a sinister vibration as the Rebels prepare for their final, desperate assault on the Emperor. And then, the audience is introduced to the Ewoks.

Their inclusion disrupts the attitude of the films immediately, and are evidence that George Lucas has lost his focus and direction for these films. As previously stated, the original Star Wars sought to marry elements of the 10 cent afternoon adventure serial with heroic myth--a sort of Volsungsaga meets Buck Rogers. But often, heroic myth is far more serious, speculative, and full of tragedy and loss, compared to Buck Rogers or Flash Gordon. Thus, Leigh Brackett's screenplay for The Empire Strikes Back downplayed the pulp serial aspect of the story, and emphasized the darker and more speculative elements of heroic myth--elements that Lucas had never included in his original story. This confusion began to bloom into full-blown schizophrenia when Ewoks first made their appearance.

The Ewoks made Star Wars schizophrenic, but the schizophrenia is merely a result, or perhaps, a symptom, of the disruption The Empire Strikes Back created both within Lucas' conception of Star Wars and the expectations of fans and viewers. When one studies The Secret History of Star Wars, one rapidly discovers that the story Lucas wants to tell changes over time. This explains a number of key plot elements that were redactively edited to make things simpler. One example is the identification of Leia as Luke's twin sister. While the identification of Vader as Father Skywalker was a brilliant fusion of a number of loose plot threads, resolving a number of script problems while producing a powerful moral and emotional reaction within both the audience and the Star Wars setting itself, the incorporation of Leia as Luke's twin might functionally resolve a number of plot holes, but they fail to satisfy the audience. The original conception of another young Jedi trainee on the opposite side of the galaxy, a female who may have to face (and perhaps provide a romantic interest for) Luke before he confronts his father, was much more appealing a concept, but was beyond the abilities of Lucas or his scriptwriters to facilitate effectively.

In other words, Lucas is no longer capable of telling the story he originally wanted to tell. Either he had lost interest in the original themes, tone, and/or mood, or his own creation had grown so far beyond his original design concept that he was incapable of reining it back in. His attempts to do so (with the Leia-Luke resolution) only succeeded in debasing his creation. His attempt to diversify his film's appeal (as per the Ewok inclusion) is more of a reflection of his marketing savvy (by that point, Star Wars had become a juggernaut in the toy industry). While it was not a bad idea from a financial standpoint, from a literary perspective, it weakened the plot's credibility. When a clan of stone-age teddy-bears manage to destroy armored mechanized assault platforms and space-age soldiers with onagers (tortion catapaults), suspension of disbelief is terminated. Until that moment, Star Wars functioned as a believable universe. Tortion catapaults require a minimum of early iron-age construction techniques and mathematics to operate, and once that is realized by the viewer, he is no longer watching a space-opera science-fiction, but instead an episode of Looney Tunes.

This dischord only intensifies throughout The Phantom Menace. Star Wars and The Empire Strikes Back had reached their perfected forms. Both movies had achieved their objectives brilliantly, without flaw or error. The utterly pedestrian resolution of the Luke-Leia problem reveals that The Return of the Jedi was not a perfectly whole creation. It could not achieve every possible goal. It did, however, succeed at some. The confrontation of Luke with his father was masterfully handled, as was his father's redemption. The destruction of the second Death Star and the defeat of the Imperial Fleet was an intensely thrilling and visually spectacular battle sequence. Luke's choice of the third path, that thin grey line between the light and dark halves of the Force, satisfies the deeper, inner battles of the heroic journey that Leigh Brackett had invoked in the previous film. Despite it's flaws, The Return of the Jedi succeeds far more often than not.

The Phantom Menace, however, is a wholly confused experience. The elements of the pulp serial are so subdued as to be virtually nonexistent (with the exception of the opening escape of the two Jedi from the spaceship). However, the emphasis on the heroic journey has now been transferred to young Anakin Skywalker. But the heroism has been reduced at the expense of the mythical (cf. his "virgin birth"). Despite claims to the contrary by modern theorists, the concept of the virgin birth is virtually absent in most of mythological and religious beliefs (with the exception of Christianity). Rather, the father is almost always a god who seduced the mother, a maiden. The inclusion of the Gungans is a far cruder, and indeed more absurd, version of the Ewok angle, and assumes that the audience is comprised not of just children, but stupid children.

Throughout the film, we are pushed and pulled through a variety of tones, moods, and atmospheres that do not set well together. At times the film is serious and political, other times it is vapidly whimsical and absurd. As a child, young Anakin Skywalker courageously races a pod and destroys an enemy starship, but, paradoxically, the Jedi Council finds him full of fear and is hesitant to train him. Lucas' screenplay has aimed at far too many targets to be able to satisfy them effectively. Thus, The Phantom Menace gives off an impression of obtuseness, especially when compared to the acuity of Star Wars and The Empire Strikes Back. The Attack of the Clones and The Revenge of the Sith showed improvements, with each crawling closer to a balance between Lucas' original vision and Brackett's adaptation of it. Yet they were unable to achieve the same tightness of plot and flawlessness of storytelling. Star Wars had become far too self-aware, and felt obligated to provide more than it was capable. Lucas, also, has shown an inability to handle fame and fortune well, and has descended from being a mildly eccentric introvert to an erratic delusional who has fanatically taken it upon himself to rewrite past history and suppress all information regarding his franchise that does not comply with his "official party doctrine." Lucas' own introversion and eccentricity undoubtedly have a role to play in the degradation of Star Wars, but they, too, are but a facet of the problem.

But these are points that have been made many, many times by folks far more verbose than I. What is important to note here, however, is the fact that The Phantom Menace is not the cause of Star Wars' disruption and devolution. Indeed, most dissatisfied fans have a tendency to blame the symptoms and never consider the source of the illness. Lucas himself is only part of the problem. In truth, he never killed Star Wars. The reality is, with Leigh Brackett's screenplay, Star Wars left George Lucas. And, despite his strongest efforts to recapture it, Lucas has repeatedly fallen short of the simple perfection that he had achieved in 1977. Star Wars had grown and "taken its first step into a larger world." Brackett had injected plot elements and an epic feeling of tragedy and triumph that Lucas was not capable of controlling. The Empire Strikes Back is the pivot-point of the saga, the fulcrum around which Lucas' career, franchise, and universe turned.

4 comments:

You hit upon something important: Lucas' screenplay for The Phantom Menace tries to cover too many different things. The prequels suffer from Lucas having limitless power as a writer, director and financier. Most of all, his producer Rick McCallum sure as hell wouldn't be using the word "no" around George.

Overall, it's important to remember that the prequels' story would've always been written by Lucas, it's just the screenplay and direction that should've been handed off to other people (just as they were on Empire and Jedi).

Really, Lucas should not have tried to reign it all back in after Empire, but he's proven himself to be a control freak.

To Mike:

He is a control freak because the experience of dealing with producers and executives touching its vision fucked him over.

This is mentioned on the "The People Vs George Lucas" documentary of 2010.

This is a brilliant analysis. I don't know that I completely agree with it - if the prequels had never been produced, no one would ever have traced your line of reasoning. But it's the kind of insightful work that shows long hours of thought and care.

I wish that you would edit this sentence, because I miss whatever thought you didn't quite complete:

"Fans rarely had a choice to remain ambivalent--the prequels were either travesties upon Lucas' vision and the proverbial axe which 'killed the goose that laid golden eggs.'"

They were either travesties or what?

Once again well done, and thanks for writing.

They were either travesties or what?

Hmmm... Mark, I wrote this so long ago... I have no idea what the "or what" was supposed to be. I don't usually let errors like that slip past me anymore so much because I write so much more often that I usually catch these errors. When I figure out what the "or what" was supposed to be, I'll give it an edit.

Thanks for reading all the same. I'm glad you got something out of it!

Post a Comment