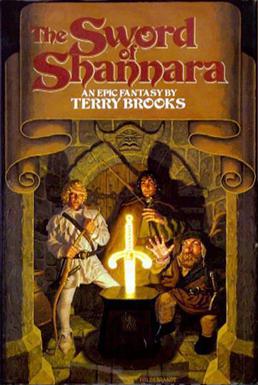

It's caught a great deal of flack for its parallels with Tolkien, but Terry Brooks' The Sword of Shannara came at a vital time in the growth and development of the fantasy genre, and played a vital role because of that. Published in 1977 (the same year as the release of Star Wars), Terry Brooks' debut novel broke from the mainstream of fantasy writing of the day by crystallizing Tolkien as the ideal model of fantasy fiction in the minds of many authors in the following decade.

They say imitation is the sincerest form of flattery. (They also say something similar about parody.) And Brooks' work is a most certain imitation of Tolkien's The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. But in a sense, that is its strength.

Just peruse the wikipedia entry for The Sword of Shannara, and you'll find a plethora of scathing criticism lambasting it for the close similarities between the two fantasy works. Very few wikipedia articles on fantasy novels have such comprehensive descriptions of reactions to a work. If you read the rest of the entry, you realize that Brooks wasn't necessarily a bad writer for "ripping off" Tolkien. Indeed, he was only 23 when he started writing, and didn't finish it until he was 30. Brooks had begun penning the novel in 1967, at the height of mid-century Tolkien fandom. It was during this time that Peter S. Beagle reports "Frodo Lives!" being scrawled in spray-paint on subway walls. The Lord of the Rings had emerged in the popular awareness as an artifact of American counter-culture. The Sword of Shannara was a product of Brooks' literary interests and the times he inhabited, and as a result it mimicked them.

What concerns most critics and reviewers, I believe, is the fact that The Sword of Shannara sold so well for being an imitation, and was deliberately packaged by the Del Reys into a successor to Tolkien. An article from the Cimmerian quotes an essay by Douglas A. Anderson[1], a Tolkien scholar:

These two people deserve a large share of the credit —or the blame —for what happened afterwards to fantasy.

Both of the del Reys were decidedly old-fashioned in their tastes, and when Judy-Lynn del Rey, soon after taking over at Ballantine, was accused of trying to set science fiction back thirty years, she didn’t deny it. Similarly, Lester del Rey, at a convention in early 1975, attempted to define what he wanted as a fantasy editor. He was asked: would he publish a latter-day ernest Bramah (author of the Kai Lung stories, which had been republished in the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series). “No, absolutely not,” he replied. What about Dunsany? “I would tell him that he didn’t need all that fancy style to tell a good story.” Basically, del Rey wanted plot and little else. The critic Darrell Schweitzer has described him as “purely a pulp editor, who saw fiction as product,” who “had no artistic pretensions at all” and who represented “that Depression-era, writer-as-working-stiff attitude at its very worst.”

The del Reys took the view that fantasy, long a very small portion of overall fiction sales, could be a real mainstream success if packaged and promoted properly. Two authors were pulled out of the slush pile to prove their theory. The first was Terry Brooks, who had submitted a slavish imitation of The Lord of the Rings under the title The Sword of Shannara. Published in April of 1977, the del Reys added some hyperbole to the cover some hyperbole of a kind that is now so commonplace as to be meaningless: “For all those who have been looking for something to read since The Lord of the Rings.

"For all those who have been looking for something to read since The Lord of the Rings" is a phrase that cannot be underemphasized, and is essentially the key to Brooks' success. None of his following novels have generated even close to this amount of criticism, despite being rather hit-or-miss (The Elfstones of Shannara being rather less derivative and containing the seeds of a better story, especially when compared to The Wishsong of Shannara, which is strangely post-modern in that it rips-off of The Sword of Shannara).

The general appeal of the book is the fact that it is an imitation of Tolkien. Prior to this publication, readers of fantasy had Lin Carter, L. Sprague de Camp, Fritz Lieber, Poul Anderson, Michael Moorcock, Anne McCaffrey, Roger Zelazny, and reprints of Lovecraft, Tolkien, and R. E. Howard (under de Camp and Carter's edits and pastiches). Tolkien's work had possessed a number of elements that all of the other writers' stories and novels did not.

First, their descriptiveness was much more terse, often pulpy (especially Moorcock and Zelazny), whereas Tolkien was verbose, complete, and evocative. This is partially due to the nature of many of their publications. Most of these authors' works were serialized in magazines, where space was at a premium. Fantasy was rarely published in novel or paperback form compared to today, and as a result, the writers became accustomed to tense, tight prose packed with a great deal of meaning in as few words as possible. Tolkien had license to explore his setting in much more immediate and minute detail. In addition, Tolkien was, like it or not, an heir to a literary legacy that includes (and is undoubtedly influenced by) Dickens, and that should say enough in itself.

Second, the stories more often than not include heroic characters that are not cut from the common cloth. Zelazny's Amberites are almost immortal for their abilities to heal and their skill at fighting, for example. Fafhrd and the Grey Mouser are adventuring scoundrels. Moorcock's Elric of Melniboné needs no elaboration, his reputation inevitably preceeds him so. Tolkien had more common characters pulled into events far beyond their own little worlds.

Third, they lacked the sense of a perilous quest against a driving, all-encompassing darkness. The threats to the characters in many of these novels was often much more immediate and personal. The characters of much fantasy during the 1960s and 1970s were arrayed against demons and demigods, but rarely against cosmic forces of darkness that sought to engulf reality. Those forces may have existed, but they were as far beyond the capabilities of the heroes to combat as the heroes themselves were beneath these powers' notice.

Fourth, they were often contained in volumes of 250 pages or less, which means that the plot had to move at a rapid pace, and could only include a limited amount of events and development. Tolkiens novels stretched for hundreds of pages per volume, resulting in a lengthy epic. In addition, they are accompanied by more than a hundred pages of appendices, containing the history of Middle-Earth, characters, stories, maps, language notes, and time lines. This added a sense of depth and realism to Tolkien's setting and characters. The length enabled Tolkien to develop personalities and plots to a much greater complexity than many other fantasy authors.

These four characteristics that were present in Tolkien were, by-and-large, not to be found in the works of many of those other authors. On the other hand, Brooks managed to infuse The Sword of Shannara with these Tolkienesque elements that slaked the public's thirst. Despite the disparagement of sword-&-sorcery afictionados, the Del Rey line revitalized fantasy through publishing The Sword of Shannara.

Though Terry Brooks is not an incredibly imaginative and dynamic author, I feel fantasy owes him a debt of gratitude. Alongside Stephen R. Donaldson's Lord Foul's Bane, epic high fantasy re-emerged, and made a great deal of other things possible. In truth, fantasy was being strangled by the pulpish scrawlings of Moorcock, Zelazny, Lieber and others who tried to continue the legacy of R.E. Howard, H.P. Lovecraft, and C.A. Smith. This, by no means, disparages their contribution or their skill as writers--I deeply enjoy the pulpy styles. However, if theirs was the only influence on fantasy after Tolkien, I feel that we would have been shortchanged as time wore on.

The immediate successors of Brooks and Donaldson, however, do not get the same degree of appreciation. The 1980s saw David Eddings' very derivative works (see Places to Go, People to Be for an interesting and informative look at Eddings that is much more objective than I am). Much of the TSR novels based on Dungeons & Dragons gaming worlds were lackluster at best (with the exception of some gems, such as Weis & Hickman's Dragonlance Legends or Jeff Grubb & Kate Novak's Azure Bonds), but to describe D&D's role in fantasy is an entire essay in itself (both in its origins and its impact). (See also, Grognardia for a hyperbolic look at Dragonlance). Thankfully, Raymond E. Feist managed to get Magician published, opening the door for his magnificent Riftwar Saga, especially A Darkness at Sethanon, a novel full of the fruits of a fertile imagination. Terry Goodkind and Robert Jordan entered the fray in the early 1990s, each beginning sagas that would drag on eternally and inaugurating an entirely new reason to gripe about developments in fantasy.

Ironically, the appeal for such writing lies in the inability for the reader to accept an ending. Thus, Brooks succeeded as a Tolkien replacement. The populace did not want The Lord of the Rings to end, and so they found they could read it again in the form of The Sword of Shannara. The desire is to have the same type of story repeated to them ad infinitum. This explains the tremendous success of Donaldson, Brooks, Eddings, and Jordan, while more original writers as Feist and Tad Williams would only come to enjoy great (not tremendous) or mediocre success.

Fortunately, that era seems to have receded, and now Tolkien-derivative works seem to be rarer these days. In their place are works that are often darker, more realistic, with a deeper base in historical reality and politics. The influence of the pulps is more pronounced in the newer fantasy as well. R. Scott Bakker's Prince of Nothing, Glen Cook's Black Company, and George R.R. Martin's A Song of Ice and Fire are more subtle, political, and morally ambiguous than much of the same stuff Brooks, Eddings, et. al. had produced, and Martin has admitted that he owes a deep debt to Tad Williams' Memory, Sorrow, and Thorn for demonstrating that fantasy could be more than "kid's stuff."

As books go, I have fond memories of The Sword of Shannara. It remains one of Brooks' better works, honestly. A few years back, I tried to reread The First King of Shannara and found it an impossible task. The book was horrendous. The pacing was a disaster and the plot felt as if it was held together by string and Scotch® tape. Upon returning to The Sword of Shannara, I was pleasantly surprised to find a lot of those weaknesses weren't present. Brooks' prose was tighter, the plot much better paced, and the development of the characters and story drew in the reader. It succeeds as an imitation because Brooks understood what he and readers wanted in a successor to Tolkien. There is deep themes of friendship and perseverance against impossible odds, struggles for thrones, noble kingdoms of men that are threatened by massive armies of evil, strange locations, different races, and thousands of years of history. When Brooks info-dumps in the early chapters of the novel, it's actually quite interesting. We get the feeling that we are sharing deep secrets and forgotten lore.

There are reasons that The Sword of Shannara was such a success, regardless of how you may despise it. The simple fact is, it was a replacement for The Lord of the Rings. The fans of Tolkien had not wanted those tales to end. Terry Brooks enabled them to experience similar emotions through his own work. And through The Sword of Shannara, Terry Brooks helped to spur a movement away from short, pulpy fantasy novels. Writers invested themselves more deeply in epic tales. Unfortunately, much of this resulted in more imitations (David Eddings' The Belgariad for example) or rampant word-bloat (Robert Jordan and Terry Goodkind). However, it also catalyzed more recent, mature, and intelligent fantasy writing that has emerged in the past decade. Like it or not, we owe Brooks a debt of gratitude for opening doors.

1 comment:

Yeah can you gib me a sumury ove pages 186 t o 367 uhm yeah thx

:^]

Post a Comment