Part Two.

Several years ago, I wrote this post, discussion the value of 超時空要塞マクロス(Choujikuu Yousai Makurosu = Super Dimension Fortress Macross) as a science-fiction drama. If you've already read that post, please bear with me because I'm going to cover some similar ground.

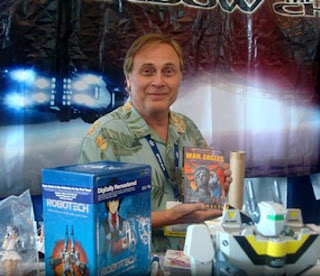

My discussion of Macross inevitably begins with Robotech. For many Generation X'ers who were children during the 1980s, including myself, our introduction to Japanese アニメ (anime = "animation") was through the various work of Carl Macek (who passed away in 2010). Macek is either a hero or a villain depending on to whom you speak. While Macek did a lot to bring アニメ to North America and other Anglophonic countries, this often required mash-ups, heavy editing, and sometimes even complete and total rewrites of entire series. The most notorious (and, indeed, his first big) project was Robotech for Harmony Gold, which took three unrelated anime, 超時空要塞マクロス (Super Dimension Fortress Macross), 超時空騎団サザンクロス (Super Dimension Cavalry Southern Cross), and 機甲創世記モスピーダ (Genesis Climber Mospeada), combined them into three consecutive generations and changed names, dialogue, and even edited out certain scenes in order to make the show more palatable to an audience primarily composed of American and Canadian children (and possibly their parents).

|

| Carl Macek |

The purpose behind the heavy editing was two-fold. First, Macek had to rewrite names and dialogue enough to explain the progressive generations and put them into a narrative framework that would make sense. Thus, for example, the Zor in サザンクロス (Southern Cross) were rewritten as the Robotech Masters, the overlords of the Zentraedi from マクロス (Macross). In addition, dialogue and visual content had to be edited to make the show fit for children, since in the 1980s it was assumed that cartoons were strictly for kids. Thus, dialogue that related to mature themes (such as sex or suicide) had to be sanitized for American child audiences. The brief and occasional nudity also had to be excised.

What was shocking, however, to me as a kid, were the abundance of mature themes and ideas that persisted. Characters died and the price of war was high. There was a continuous narrative that flowed from episode-to-episode. This was during a time when G.I. Joe and The Transformers were self-contained, independent stories and it mattered little if you missed a few episodes. Robotech was the first show that I made certain I watched daily as a child. If I missed episode 13 of G.I. Joe, I could still pick up and watch episode 14 the next day because Cobra Commander would be hatching a completely new and unrelated plan. Missing an episode of Robotech meant that I missed out on character and plot development.

In addition, when a plane was shot down in Robotech, there wasn't always a parachute to let the censors know the pilot escaped. People died, good and bad. Robotech was about war and the cost of war. Robotech challenged me far more than the other television cartoons that I viewed and it inspired me to a wider and more complex world of stories and storytelling.

I'm not writing this series of blog entries, however, to discuss Robotech. I'm writing a retrospective that will analyze and review 超時空要塞マクロス (Super Dimension Fortress Macross). To that end, I want to discuss first how Macross came about and then, in subsequent posts, explore the narrative elements and themes of the series.

|

| Kawamori Shoji |

Macross was the brainchild of 河森 正治 (Kawamori Shoji), an animator, designer, and conceptual artist who began working in the Japanese animation industry during the late 1970s. His influence as a designer is extremely heavy--he's done designs for Matsumoto Leiji's Space Battleship Yamato and even had a hand in creating a number of Generation 1 Transformers. If you've seen Eureka 7, the Patlabor movies, the Ghost in the Shell film, Mobile Suit Gundam 0083: Stardust Memory, Outlaw Star, or Vision of Escaflowne, you've seen mechanical designs by Kawamori. Kawamori got his big start working as an intern and assistant artist at スタジオぬえ (Studio Nue), which produced Matsumoto's Space Battleship Yamato in 1974. Kawamori would eventually come to helm 1996's 天空のエスカフローネ (Vision of Escaflowne) at Studio Nue before branching off to create many science-fiction and fantasy anime that would come out during the new century, particularly 2001's 地球少女アルジュナ (Earth Maiden Arjuna), 2005's 創聖のアクエリオン (Genesis of Aquarion), and 2012's AKB∞48. However, he always seems to return to the universe of Macross from time-to-time, revisiting it with Macross Plus, Macross 7, Macross Zero, and most recently, Macross Frontier.

Macross is a foray into what is known as the リアルロボット ("real robot") genre in Japan . The basic idea of this genre centers on

somewhat explainable scientific and technological advances that make possible

the construction and piloting of giant robots.

The first true real robot series is usually considered to be Mobile Suit

Gundam, and Kawamori’s Choujikuu Yousai Makurosu helped to better define the

tropes and characteristics of the genre.

This genre is noteworthy for its departure from other giant robot shows

like Voltron because the core concepts are more realistic, don’t rely upon gimmicks

like “blazing swords” and “monsters of the week,” focus on weapons that are

known to be technologically possible, don’t have special attacks that are

activated by voice-command, and so on.

In Part One, I will give a brief overview of the plot for 超時空要塞マクロス (Super Dimension Fortress Macross) and initiate discussion of its more salient themes as well as occasionally compare it to other popular "real robot" anime, especially Mobile Suit Gundam.

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment