Other authors and blogs have spent copious gigabytes describing why Tolkien is (or isn't) a major landmark writer in fantasy and how his works are integral to the literary canon of the 20th century. Tad Williams, by-and-large, gets ignored by the fantasy-reading public and the elitist English professor alike and this is a damn big shame. So, instead of reviewing Williams' novels or only describing how they fit into the overall historical schema of mainstream epic fantasy's evolution, I'm going to do some analysis and explain what Williams got right. Thus, it seems fair to warn the reader that THERE ARE SPOILERS AHEAD! You've been warned, dear reader.

The Beginning

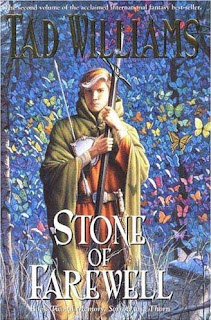

The BeginningIn 1988, DAW Books published The Dragonbone Chair, a novel nearly 700-pages in length with an entirely uninspired-looking map (more highly detailed maps would be found throughout the text itself), an appendix that glossed people, places, and things in Osten Ard, and a translation guide for phrases in different languages. Most readers never got past the first 200 pages of exposition in the novel, arguing that "nothing happens" (which puzzles me, because much of books 6 through 9 of The Wheel of Time feature gratuitous amounts of nothing happening until the last 150 pages and people love Robert Jordan).

So, am I just insane or is there something here the average reader missed?

Well, the first 200 pages of The Dragonbone Chair are exposition. Williams is carefully, subtly establishing a typical medieval setting, its political situation, its characters and their feuds, loyalties, goals, and relationships. He's also instilling the reader with a sense of status quo--the world works like such, magic and faeries are just stories and reality is just mundane. Then, when the reader is about a quarter of the way through the book, all of the readers assumptions are destroyed, the status quo is irrevocably overturned, and all hell seems to break loose. This happens so rapidly as to shock the reader. After 200 pages, the reader's become subtly invested in the world, the characters, and come to feel that he/she can predict where things are going when Williams turns the tables and tells us to take nothing for granted.

The Cliche

The ClicheWilliams draws from medieval romance, just as David Eddings had done. However, Williams does it in a way that preserves the sense of wonder and mystery about his setting in a very Tolkienesque manner. In other words, Williams not only mimics Tolkien's style but also his atmosphere. Osten Ard is a layered setting--there's the mundane world of humans but underneath it lies the innate magic and mystery of the setting and its more subtle inhabitants. Now, Osten Ard does not feel like Middle-earth but more like the magical medieval England that never was, the one that knew King Arthur, Lancelot, and the Knights of the Round Table.

Memory, Sorrow, and Thorn centers around an epic quest in search of powerful McGuffins (in the form of three legendary swords) that the characters hope will save them from the Storm King. Knighthood (and boys who daydream of becoming knights) plays a powerful role--righteous behavior, faith, and bravery are cherished by many of the noble characters in the series; the heroes ultimately strive for something greater than themselves, even though most of the time they're concerned with mere survival. The good guys are guided by Nisses' Du Svardenvyrd (the Weird of the Swords), a book of prophecy. One particular character happens to be descended from kings and rightfully deserves the crown, although he doesn't necessarily know it (or even want the crown). A rebellious princess seeks to escape the prison of palace life and ends up embroiled in events beyond her knowledge and maturity to handle. The faerie races feature heavily in this book, although somewhat subtly, as Williams seems to understand that familiarity breeds contempt. Much of the series is bildungsroman, focused on Simon's growth from a young boy into a hero. Finally, many of the countries and religions in Osten Ard have real-world analogues that should make them more familiar to the reader (Erkynland = England, Nabban = Byzantium/Rome, Hernystir = Wales/Ireland/Scotland, Rimmersgard = Scandinavia, the Thirthings = Magyars/Huns, Perdruin = Venice/Genoa, Aedonite Church = Catholic Christendom).

These things are all very-well established tropes that have cropped up throughout heroic epic fantasy since Tolkien. At first blush, Simon will remind readers of Garion from Eddings' The Belgariad, Pug from Feist's Magician, and Taran from Lloyd Alexander's The Chronicles of Prydain. The Storm King ruling from his far northern kingdom will no doubt remind readers of the demonic, supernaturally powerful dark lords found in fantasy from Tolkien on (including Jordan, Alexander, Eddings, Brooks, and others). What Williams establishes is a status quo not only of setting, but also of technique and material.

But where the other authors simply sought to retell the same old tale, Williams had the talent to do things that were unique and different. He doesn't just imitate the story elements of Tolkien, Mallory, and Chaucer. He seeks to incorporate an atmosphere, sense of wonder, and thematic substance.

Literature and Substance

Literature and SubstanceHeroism, Combat, and Death

George R.R. Martin was initially inspired by Tad Williams' Memory, Sorrow, and Thorn to write a mature, intelligent fantasy. It's a shame that Williams doesn't get quite as much credit as he deserves and Martin has definitely eclipsed Williams' popularity. It would be unwise, however, to compare A Song of Ice and Fire with Memory, Sorrow, and Thorn. Williams and Martin are attempting to do very different things with their respective series, and Martin's work is not yet finished. Williams explores themes that Tolkien never had. Tolkien's archaically poetic voice matched his equally archaic subject-matter. The Lord of the Rings features a lot of elements subversive to heroic quest literature but Williams challenges themes that Tolkien overlooked.

Williams' voice is deep and mature. The characters are dynamic, driven, and evolving. Simon grows and changes, but he does not do so in a vacuum. Unlike Tolkien, whose characters saw many things and did many deeds, but ultimately (except for Frodo), remained the same as before, Williams' characters are unmistakably changed by their experiences. And with good reason--they experienced something so horrifically terrible, it would be ridiculous for them to simply go on as if it had never happened.

Now, this is not being entirely fair to Tolkien--his characters do change. But after their adventure, the greatest shift that occurs is the world becomes a bit more mundane (the Elves leave, the King returns, and Hobbitism continues as it always has, with that brief interruption from Sharkey). In comparison, however, the changes in Tolkien's world are much more superficial. In Williams' work, the entire world is ripped apart in the struggle over King John's throne. Alliances are made and broken, and when the dust settles, no one's demesne is as it was before. Characters have either been forced to become great heroes or have been broken and/or killed. I am reminded of Catherine Barkley's axiom in Hemingway's A Farewell to Arms, in which she says that the world breaks everyone, and if it cannot break them it kills them. Williams offers a third alternative--those that aren't broken or killed become heroes.

But being a hero isn't a happy thing. Simon's first taste of warfare is bloody, horrific, and ultimately unromantic. Despite all of the romantic elements that dwell on the surface of Williams' epic, there are deep challenges that flow deep below. Simon's knighthood is rewarded with a troop of men that he leads to their deaths beneath his new banner. He watches friends and comrades die and kill around him, and is shocked to numbness by the smells, sounds, and sights of the battle. His senses are assaulted and he, in a primitive echo (or perhaps, foreshadow) of the great Sir Camaris (Williams' Lancelot), is a demon in battle who weeps for the men he smites.

Being a hero means loss. Being a hero means overcoming the agony and pain of one's circumstances. Like a Homeric epic, Williams' heroes display ἀρετή (arete), but when they are alone, the pain wells up and they lament for themselves and for those around them. Thus, one of the most noteworthy characteristics of Memory, Sorrow, and Thorn is the role of war, death, and combat. Characters die. Combat is lethal. Wounds can result in disfigurement and death. In many epic fantasies, the main characters seem to be immune to the dangers of combat (unless the author has literary reasons for killing one or two off). Williams is never afraid to have an encounter result in half the party being slain--a far more realistic depiction of combat than what is common in mainstream epic fantasy.

Symbolism

Another element that runs strongly throughout Memory, Sorrow, and Thorn is symbolism. Williams' keenly infuses a great deal of meaning into the three eponymous swords that give the series its title. The names of the swords: Memory, Sorrow, and Thorn, are reflective of the thematic weight they bear.

Minneyar (Memory) was forged from the keel of a Rimmersman's ship when they settled in Osten Ard from across the sea. It was made of metal not found in Osten Ard and bound by the Dwarrows with the Words of Making. It wasn't of Osten Ard at all, and it's alienness made it powerful. It was carried to the Sithi stronghold of Asu'a, and was there when the faeries were slaughtered beneath the cold-wrought iron of the heathen Rimmersmen.

Thorn was made from the meteoric iron found in the meteorite that destroyed the Temple of Yuvenis the night after Usires Aedon was hung from the Execution Tree. Again, Dwarrows forged the blade with the Words of Making. Again, it was not of of Osten Ard, but of alien origin.

Jingizu (Sorrow) was forged by the Sithi prince Ineluki, when their city of Asu'a was being destroyed by the Rimmersmen. It was a blend of iron (poison to the Sithi) and their mystical witchwood, and was bound together by the Words of Making. It was named for Ineluki's lamentations as he wept at the loss of Asu'a and the destruction of his beautiful people.

These three blades each carry a legacy and each forms a major theme in the book. Memory symbolizes the cruelty of man and the memory of the faerie. It also symbolizes the memories of the characters and the harms that have been done. Disguised by Prester John, it is also given additional meaning--memory in the face of a lie. Prester John may have been the greatest king in Osten Ard, but he was also a liar, and the memory of his lie pursued him to his death. Simon ends up bringing Memory to Ineluki at the climax of the story.

Sorrow is obvious. The book is filled with loss. The Sithi lost their kingdom, and they broke with their bretheren, the Norns. They came fleeing from the dreamlike world of the Garden to Osten Ard and brought the evil they sought to escape with them. Theirs is a tragic tale. And Ineluki's search for vengeance and the emptiness of his very soul as he continues in Undeath (or Unbeing) is filled with sorrow and fury. The themes of Sorrow and Memory are closely tied together here. Sorrow is borne by King Elias, who laments the loss of his wife, and was willing to throw his very kingdom away in a mad gamble to get her back through black sorcery.

Thorn is redemption. Christ's head was pierced by thorns, and his hands by thorns of iron. Thorn is a great, black iron sword wielded by Sir Camaris. Sir Camaris, like Lancelot, is the greatest knight in Aedondom. He explains how battle is the vocation of the knight because it is the way God decides the fate of nations on the earth. It has a will and a mind of its own. It can only be wielded when the cause is righteous. The connection between thorn and Usires Aedon is vital to its identity. Simon carries Thorn for a time, although he is not it's master. Camaris spends much of his time in guilt and internal turmoil, begging forgiveness for God for his sins, both on the battlefield, and off. He inevitably is there at the climax, carrying Thorn when he meets Elias and Simon before Ineluki.

Faith & Redemption, Forgiveness, and Dark Lords

In the presense of all three, Simon stands at the crux. Instead of throwing a ring into a fire or blasting Ineluki with magical fire, he forgives him. He extends sympathy. He refuses to hate. The climax of the book stands alone amongst epic fantasy.

In this respect, Williams' differs sharply with his colleagues in the epic fantasy business. Tolkien's Dark Lord Sauron is destoryed when his Ring is destroyed--he was truly dead, but continued to exist through the Ring. His motivation was to continue the work of his master, Morgoth the Enemy, but for some reason, his objectives were vague beyond the cryptic "cover the world in darkness" routine. Brona, the Warlock Lord of The Sword of Shannara used sorcery to remain a powerful wraithlike creature, bound to the material world through lies of magic, lies which were broken when touched by the Sword of Shannara. Terry Brooks' evils in Shannara all have equally vague objectives, which in the end boil down to "cover the world in darkness". Takhasis, the Queen of Darkness in Dragonlance, was defeated through heroic bravery and by the supposed innate nature of evil to consume itself.

Williams' provides his evil characters with much more depth. In the end, this makes them less vague and distant, less unfathomable. At the same time, it makes them much more sinister and inhuman. They have traded in all of their other drives, desires, and emotions for the few negative feelings that now sustain them. The Norn Queen longs for the lost past, and seeks to Unmake reality, because she has grown so egocentric over the long march of millenia that she cannot imagine the world continuing without her. Ineluki, the Storm King, however, thirsts for vengeance. His life ended in sorrow, which is why he named his sword Jingizu (Sithi for "Sorrow"). Yet in death, he found no release, and, sustained by black sorcery and hatred, he perservered. Unlike the other undead monolithic evils of epic fantasy, the Storm King was sustained by mostly his own emotions--by hatred and the desire for vengeance. He wanted to inflict the same sorrow upon the humans that they had caused him.

The defeat of these epic beings does not necessarily involve the wielding of great talismans against them. Indeed, for most of the books, the characters have no idea how they will use the Three Swords that seem to be their only hope to defeating the Storm King. Nevertheless, the weapon that defeats Ineluki is forgiveness and sympathy. Simon tells Ineluki "I will not hate you." The most powerful talisman that can possibly be held against evil is the human heart.

This ties in with the final point I'd like to make. The role of Christianity in Memory, Sorrow, and Thorn. Williams presents a start contrast to his contemporaries in epic fantasy again by placing the Church in a much more positive role than other epic fantasy. But he plays it subtly. The Aedonite Church is rife with corruption, just like the true historical church. However, it is a source of faith for many of the characters, and those characters who are the strongest in their faith place their faith in God--the Church is simply their vehicle, and not the object, of their affections. The "holy father" of the church is a man of great wisdom, faith, and justice. In many ways, the Aedonite Church represents the Catholic Church as it should have been, but unfortunately for history, wasn't.

The most telling scene is where Pryrates, King Elias' advisor and a powerful sorcerer, attacks the Lector (the analogue for the Pope). Father Dinivan stands between Pryrates and the Lector's rooms, armed only with his wooden tree (their version of the Crucifix). And the faith that Dinivan displays balks Pryrates--momentarily. Although Dinivan is defeated, he severely wounds Pryrates. Although the action between the Lector and Pryrates is not described, the sorcerer reports to King Elias that the lector was a very powerful man, while wincing as if remembering the wounds that he received--wounds that most certainly would not have been physical, but spiritual.

Magic, Spiritualism, and Faerie

Magic, Spiritualism, and FaerieI could continue to elucidate a variety of points that make Memory, Sorrow, and Thorn an incredibly unique tale. Williams takes a vast number of epic fantasy and chivalric romance tropes and imposes them upon a framework which warps them into a shape that is entirely new and challenging.

It is worth mentioning, however, a number of excellent adaptations that he's made in his books.

Magic and sorcery are magical and sorcerous again. Pryrates has much more in common with Tsotha-Lanti or Xaltotun from Robert E. Howard's stories than he does with Gandalf, Rastlin, or Allanon. Magic is incredibly subtle and unnatural. It twists the fabric of reality. When the Dwarrorws explain how the Words of Making work, they are emphatic that they are powerful and grave to use, because they force things to take shape that, by all intents and purposes, shouldn't be. Like reversing gravity, or cancelling it's effect whatsoever.

This ties in with the nature of the Sithi. They are, like the faeries from White Wolf's Changeling: the Dreaming, from another world, although it's spoken of as a geographical location. Williams' is purposely vague, because the reader is supposed to fill in the blanks. They could be from space, or they could be from a dreamlike realm beyond the wall of sleep. Their magic is songlike, a mixture of words and tones that creates and effect. It also makes their form of sorcery very liturgical and ritualistic, but not in the manner that most sorcery is imagined.

In addition, the battles between the Norns and the Sithi are the best description of a fight between faerie peoples that I have ever read. How the Sithi and Norn songs counter one-another, and how their hand-to-hand combat is dancelike and lethal, almost like snakes striking at one another, is incredible.

There are still more and more themes and threads that I could discuss about Memory, Sorrow, and Thorn. The series is, perhaps, the best piece of epic fantasy that I've ever read. Like Frank Herbert's Dune, it seems like a straightforward struggle between Good and Evil, but also like Herbert's work, Memory, Sorrow, and Thorn deals with themes and concepts that strike far beyond the boundries of the conventional epic fantasy. Williams challenges the pre-established notions of what an epic fantasy is by re-inventing almost all of its major characteristics. Nothing remains untouched. Nevertheless, when the book is finished, you've still experienced all of the things that make epic fantasy great.

I'd like to also note that Williams turns a lot of established cliches and tropes on their ears while preserving the mythopoeic feel that should permeate epic fantasy. He's done more than simply imitate Tolkien. He took the trappings of Tolkien, Chaucer, and Mallory and done something meaningful with them. In the end, he ties things up and closes the book. In the twenty years since Memory, Sorrow, and Thorn was concluded, Williams has not returned to Osten Ard. That story was told and finished. By allowing it to end, he has preserved the substance and meaning of his tale without diluting it with a never-ending cycle of publications.

In some ways, Memory, Sorrow, and Thorn should provide a sort of model regarding how to write heroic epic fantasy without falling into the traps that Tom Simon elucidated. I find it quite telling that George R.R. Martin, though inspired by Tad Williams, does not imitate his style or substance, instead reaching for and developing his own in A Song of Ice and Fire. This is why Williams' contribution to fantasy is so important. While Eddings, Brooks, Jordan, and Goodkind were churning out epics that used Tolkien and his sources as a model to imitate, Williams took that model and not only told a story but sought to explore a variety of themes that speak to the human condition. Although he was largely overlooked by the mainstream fantasy-reading public, the authors that mattered noticed him and set about to break fantasy out of the cliche-ridden repetitiveness, meandering and pointless plotting, and vapid attempts at philosophy that had infected it.

9 comments:

I would hazard a guess that the reason William's work isn't more popular is precisely becuase he hasn't continued tales of Osten Ard. If you go to his website, there are dozens and dozens of threads asking why or when more will be forthcoming.

He denied the masses what they wanted, and has been shunned as a result.

I'm just about finished with his Shadow series.. and I really don't care for it nearly as much.. it just seems to much like a re-hash of Osten Ard.. to at the same time not be Osten Ard.

I won't argue that Williams' reluctance to continue writing about Osten Ard has led to a diminished popularity. I've not read Otherland but I heard that it got mixed reviews and many readers don't prefer it. As for the Shadow series, it is possible that Williams has just run out of stories to tell. Or, perhaps, he's trying to write more epic fantasy to please the publishers/readers. I dunno. I haven't read the Shadow series either.

I mean don't get me wrong.. it's not a bad series.. but it's got sort of angsty semi-malevolent elves as the bad guys.. but really dosen't have any characters who are as strong as those from the earlier series. While at the same time having this constant looming threat of a semi-persio-arab race from the south coming to slay the infidel for not believing in their god king and may or may not be trying to bring back the old gods that the elves went to war with..

I'm going to give War of the Flowers a read next.. I don't have Otherland yet.

I heard War of the Flowers wasn't all that good, but this is coming from a person that enjoyed The Name of the Wind. I still have to read the link from Dave's previous post, but I know I wasn't much a fan of the writing style.

As for Otherland, I got about halfway through it, but only stopped reading due to a variety of distractions. It was easier to read in College. However, the book series isn't really worse or better, as it is simply different. You can definitely tell it is written by the same author, but the very nature of the story is completely different to what is being told in Memory, Sorrow and Thorn.

In truth, fans can be the worst thing to happen to an author. Feedback is good, but fans will want more of the same while wanting something different at the same time. It could be that Tad Williams doesn't have another story to tell in Osten Ard, which is completely fine. If one day he gets an idea on how to continue it, then sweet deal. But the worst "creativity" is forced creativity.

In regards to the conclusion of Memory, Sorrow and Thorn, wasn't it that the magical McGuffins were actually a trap at the end? I might be thinking of something else, but I'm pretty sure getting all three swords together turned out to be a bad idea at the end that no one realized.

Oh absolutely.

As much as I'd love to spend more time with the characters, no bones about it, I grew to love, in Osten Ard. I'd rather he not force himself to do it, not every series has to be have a sequel.

But I've also not enjoyed William's other work nearly as much.. I'm now only about 400 pages from completing the Marchlands series.. and I still feel like I'm waiting for it to get going.

It's funny, the authors you name the "true" successors of Tolkien are exactly the ones who didn't fall in for exact imitation. Perhaps it's best to say that these writers found their own voice and message, rather than try to replicate someone else's (and fail miserably at it in the process)?

Great article!

You present plenty of good arguments why this is an outstanding Fantasy series, including points and concepts I had not thought of myself.

Now, I read this series back in 1996, when I was slightly less than half my current age, so quite some time has passed since. Certain details are a bit fuzzy in my memory, to say the least, but a surprising amount has actually stuck.

Williams is a bit of a slow narrator, with massive amounts of pages to set up his story (it happens in Otherland, too, of which I have only started the second book to date)*. That didn't always sit entirely well with me as a teenager. It wasn't a series for quick satisfaction. However, I am certainly not going to hold that against the series, especially since he does manage to paint a rather fascinating world. He does manage to avoid copying Tolkien, as you say.

The tone and atmosphere is fantastic on quite a few occasions. However, it is also dark, and sometimes depressingly pessimistic (and having a sad theme about loss, which you bring up, does not help). It never seems as if the heroes have much hope of winning. Of course, they would have if they knew that the prophesy of the swords saving them being false (just wait for Storm King's window of opportunity to return to pass, because he can't do it without the swords. That fake prophesy (the False Messenger) is the best idea in the series, in my opinion.

However, for all the good points of this series, I can't claim it matches Tolkien. Not in my opinion. While imaginative, it feels like a slightly less carefully crafted world than Arda. Some things make just a little bit less sense.

The one thing that bothered me was Amerasu's seemingly total lack of any magical strength to defend herself. She is the mother of the Storm King, for crying out loud. She also comes off as totally defenseless against Ingen Jegger. Yes, I know it is partly explained; it strongly hinted that one has to be half mad and accept a rather extreme price to attain truly massive amounts of personal supernatural power in this world, and it may not be that magic is inherited. Still, the magical defenses around the Sithi home (forgot the name) seem very strong, and requires Utuk'ku to help them get through. Amerasu seems very scholarly, and she seems worried about her son's path, so why has she learned nothing to defend herself?

It seems analogous to if Sauron had one living family member left, and that person would have no more magical power to fend off an attacker than an average elf.

Again, Amerasu would not need to have magical powers on nearly her son's level, but putting her below Pryrates is pushing it (given who she is, she should probably be logically be magically stronger than that dark priest), in my opinion. I can't prove this as a plot hole, of course, but Amarasu's total lack of combat useful magic does feel slightly off (which means I buy it less), even taking into account all the explanations. Tolkien never really asks the reader to accept power gaps like this with vague explanations, and when I read Tolkien's backstory, I understand where Sauron's power comes from, and that part fits together better than this. Amerasu's failed resistance and death seems more plot demand driven than in-universe logic driven.

Well, I suppose that is a minor nit pick, and I probably come off as pedantic and/or power obsessed for pointing it out.

Sorry about the length of my post. And again, great review!

* The probable explanation why people put down Dragonbone Chair in the first 200 pages (when Wheel of Time gets away with a lot more "nothing" in the volumes in the middle of that series) is of course that they are not invested in the world yet. When Jordan gets to the slow storytelling parts, he has already set up his world, and many readers want to know what comes next. Nevertheless, I don't think Jordan entirely gets away with it, either, because I have heard of people putting down the series during those volumes.

Good news! Williams will be returning to Osten Ard, with new books, the first of which is scheduled to come out next year! :)

I'm so, so happy.

It's been confirmed that Tad Williams is returning to Osten Ard with a trilogy sequel. See his official website for more info. The first book is mooted for publication in 2016.

Post a Comment